Introduction

Arthropod pests limit production in the goat industry in many ways. External parasites feed on body tissue such as blood, skin and hair. The wounds and skin irritation produced by these parasites result in discomfort and irritation to the animal. Parasites can transmit diseases from sick to healthy animals. They can reduce weight gains and milk production. In general, infested livestock cannot be efficiently managed.

Lice

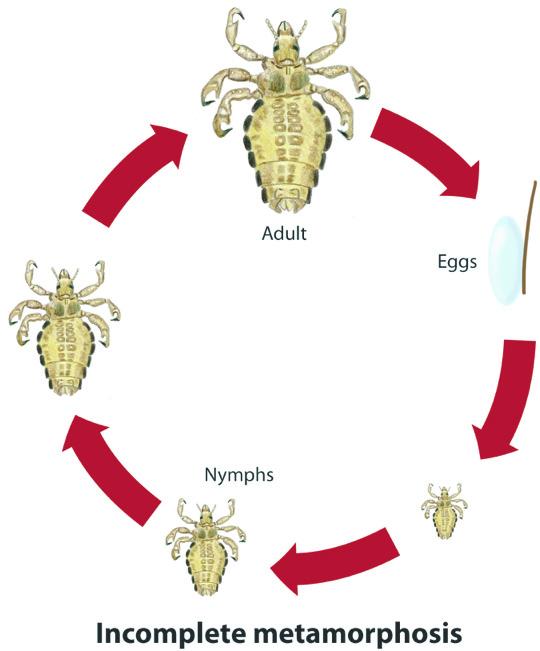

Lice (Order: Phthiraptera) are wingless, flattened, permanent ectoparasites of birds and mammals. The development of lice is slightly different when compared to other external parasites. They go through incomplete development, where the immatures are known as nymphs and look similar to adults (Figure 1). More than 3,000 species have been described, mainly parasites of birds. Lice infest a wide range of domestic livestock, including pigs, cattle, goats and sheep, causing a chronic dermatitis (pediculosis), characterized by constant irritation, itching, rubbing and biting of the hair or fleece. Goat lice are host specific and only attack goats and their close relatives such as sheep.

Bạn đang xem: Extension

Lice are divided into two main groups: the Anoplura (sucking lice) and Mallophaga (chewing or biting lice). Biting lice have chewing mouthparts and feed on particles of hair, scabs and skin exudations. Sucking lice pierce the host’s skin and draw blood. Louse-infested animals may be recognized by their dull, matted coat or excessive scratching and grooming behavior. The irritation from louse feeding causes animals to rub and scratch, causing raw areas on the skin or loss of hair. Weight loss may occur as a result of nervousness and improper nutrition. Milk production is reduced up to 25 percent. Also, the host is often listless and in severe cases, loss of blood to sucking lice can lead to anemia.

Lice are generally transmitted from one animal to another by contact. Transmission from herd to herd is usually accomplished by transportation of infested animals, although some lice may move from place to place by clinging to flies. Lice are most often introduced to herds by bringing in infested animals.

Figure 1. Illustration of an incomplete lice life cycle. Credit: Langston University

Goat lice can be controlled by both production practices and chemical intervention. Providing a high-energy diet can be an effective louse control strategy. If possible, it is important to keep animals in uncrowded conditions and to spot treat or quarantine any infested individuals until they have been successfully deloused. Most louse populations on animals vary seasonally, depending on the condition of the host. Louse populations on livestock are typically greater during the winter months and reach peak activity in late winter and early spring. Animals under stress will usually support larger louse populations than found under normal conditions. Insecticides are usually best applied in late fall. Control of louse infestations is needed whenever an animal scratches and rubs to excess. Louse control is difficult with just a single insecticide application, since they will not kill the louse eggs. A second application is needed two weeks after the initial treatment to allow the eggs to hatch.

There are three principle species of biting lice and sucking lice that can attack goats.

Biting Lice

The goat biting louse (Bovicola caprae), Angora goat biting louse (B. crassipes), and B. limbata are the three main species found on goats (Figure 2). All three species live on the skin surface and feed on hair, skin and detritus. Eggs hatch in nine days to 12 days and on average, the entire life cycle is completed in one month. Biting lice of goats are distributed worldwide with winter populations being the most severe. Optimal control can be achieved with a residual insecticide spray with retreatment in two weeks after the initial treatment.

Figure 2. Goat biting louse, Bovicola caprae (left), Angora goat biting louse B. crassipes (center), and B. limbata (right). Credits: K.C. Emerson Entomology Museum, Stillwater, Oklahoma and http://www.ento.csiro.au

Sucking Lice

Three species of blood-sucking lice are found on goats: the goat sucking louse (Linognathus stenopsis), African goat louse (L. africanus), and sheep foot louse (L. pedalis) (Figure 3). The goat sucking louse can be dispersed over the entire body of goats and the African goat louse is usually around the head, body and neck regions. Both the goat sucking louse and the African goat louse are bluish-gray in appearance. The sheep foot louse is an occasional pest of goats and can be found on the feet or legs of the animal. These blood-feeding lice species cause the most severe damage. Excessive feeding causes scabby, bleeding areas that may lead to bacterial infection. Mohair on Angora goats may be damaged to the extent value reduction is 10 percent to 25 percent. Control can be obtained utilizing the same methods described for biting lice.

Figure 3. Goat sucking louse, Linognathus stenopsis (left), African goat louse, L. africanus (center), and sheep foot louse, L. pedalis (right). Credits: K.C. Emerson Entomology Museum, Stillwater, Oklahoma and http://www.ento.csiro.au

Nose Bot Fly

The nose bot fly exhibits a unique quality by depositing live larvae (maggots) in the nostrils of goats (Figure 4). Other fly species lay eggs. Larvae migrate to the head sinuses and, after development, migrate back down the nasal passages, dropping to the ground where they complete development. Migration of the bot larvae to and from the head sinuses causes nasal membranes to become irritated and secondary infections can occur at the irritation sites.

Infested animals exhibit symptoms such as discharge from nostrils, extensive shaking of the head, loss of appetite and grating of teeth. Another sign of a nose bot infestation is the presence of blood flecks in the nasal discharge. The behavior of goats in the presence of adult bot flies is very excitatory and usually animals will snort with their noses towards the ground.

Ivermectin is highly effective against all stages of the larvae. Other drugs reported to be effective include eprinomectin and doramectin. In the U.S., these drugs or recommended routes of administration may constitute extra-label use, requiring a valid veterinary-client relationship and an appropriate withdrawal time for slaughter purposes. Nose bots are usually a winter problem, so treatment should be administered after the first hard frost, which kills the larvae internally and reduces the risk of adult flies from laying eggs for later reinfestations.

Figure 4. Nose bot (inset & outlined with square) inside the nasal passage of a goat. Credit: Langston University.

Keds

Keds, more often called sheep ticks, are actually a wingless fly (Figure 5). They spend their entire life cycle on sheep or goats, transferring between animals by contact. Sheep keds, Melophagus ovinus, are primarily a pest of sheep, but occasionally are found on goats. Adults are grayish-brown, six-legged, and 1/4-inch long with a broad, leathery, somewhat flattened, unsegmented, saclike abdomen covered with short spiny hairs. Sheep keds can live up to six months, during which time the female produces around 10 to 15 young at the rate of one every eight days. Reproduction is continuous, though slow during the winter, producing several generations per year.

Unlike most insects, the female sheep ked gives birth to living maggots, which are nourished within her body until they are fully grown. The maggots are 1/4-inch long, whitish, oval and without legs. The skin turns brown within a few hours after birth and forms a hard puparium (case) around the larva. These cases are often called eggs, nits or keds. Adult keds emerge from the pupal cases in two weeks to five weeks, depending on temperature. They crawl on the skin and feed by inserting their sharp mouthparts into capillaries and sucking blood, much like a mosquito. This feeding results in considerable irritation, which causes the animal to rub, bite and scratch. Another effect observed from animals infested with keds is the condition known as “cockle.” Hide buyers downgrade skins with “cockle” because it weakens the hide and discolors them.

Keds usually do not cause great damage if the animal is fed on a highly nutritious diet, but goats grazed throughout the year on pasture or range may acquire heavy burdens of keds during winter months and early spring. In addition, keds in large numbers can cause anemia, which can weaken the animal and make it more susceptible to other diseases.

Sprays, dips and hand-dusting with insecticides are all effective methods for controlling sheep ked.

Mites

Xem thêm : JOY REID USES ALOPECIA STRUGGLE OF PRESSLEY AS A WARREN COMMERCIAL

Goats can be infested by several species of mites, but the species more commonly found on goats are goat follicle mite (Demodex caprae), scabies mite (Sarcoptes scabiei), psoroptic ear mite (Psoroptes cuniculi), and chorioptic scab mite (Chorioptes bovis) (Figure 6).

Figure 6. left to right Goat follicle mite, (Demodex caprae), scabies mite (Sarcoptes scabiei), psoroptic ear mite (Psoroptes cuniculi), and chorioptic scab mite (Chorioptes bovis). Credits: S.J. Upton, Kansas State University and Thomas Nolan, University of Pennsylvania.

The goat follicle mite causes dermal papules and nodules, and the resulting condition is known as demodectic mange in goats. These papules or nodules are caused by hair follicles or gland ducts becoming obstructed and producing these swellings, trapping the mites within these lesions. These continue to enlarge as the mites multiply, sometimes reaching several thousand mites per lesion. Cases of demodectic mange occur most commonly in young animals, pregnant does and dairy goats. Papules usually appear on the face, neck, axillary region or udder and these papules can enlarge to 4 cm in diameter as mites multiply. Nodules can rupture and exude the mites, resulting in transmission of the mite to other animals. Transmission of the goat follicle mite to newborn goats typically occurs within the first day following birth. Other possible means of transfer are licking and close contact during mingling or mating. Certain breeds of goat (e.g., Saanen) tend to be much more sensitive to demodectic mange than others.

The scabies mite burrows into the skin of its host, causing varying degrees of dermatitis, a condition known as sarcoptic mange. Although cases of sarcoptic mange in goats often resolve themselves without developing severe signs, heavily infested goats may exhibit crusty lesions and extensive hair loss around the muzzle, eyes, and ears; lesions on the inner thighs extending to the hocks, brisket, underside and axillary region; dermal thickening and wrinkling on the scrotum and ears; and dry, scaly skin on all parts of the body, especially in areas of hair loss.

The psoroptic ear mite or ear mange mite causes lesions on or in the ear of the host animal. These lesions cause crust formation, foul odor discharges in the external ear canal and behavioral responses such as scratching the ears, head shaking, loss of equilibrium and spasmodic contractions of neck muscles. Psoroptic ear mite lives its entire life under the margins of scabs formed at infested sites. The eggs are deposited and hatch in four days. The complete life cycle takes about three weeks. All stages of this nonburrowing mite pierce the outer skin layer. Transmission of this mite occurs between animals by direct contact. Prevalence rates as high as 90 percent in the U.S. have been reported in dairy goats, including both kids and adults. Goats usually less than one year old generally exhibit higher infestation rates than do older animals. Signs of the psoroptic ear mite in kids are often observed as early as three weeks after birth, reflecting transfer of mites from mother to young. By six weeks of age, most kids in infested goat herds are likely to harbor these mites. Chronic infestations can lead to anemia and weight loss in goats.

The chorioptic scab mite causes chorioptic mange in domestic animals, especially in cattle, sheep, goats and horses. This mite occurs primarily on the legs and feet of its hosts, where all of the developmental stages are likely to be found. Eggs are deposited singly at the rate of one egg per day. Eggs are attached with a sticky substance to the host skin. Adult females usually live for two weeks or more, producing about 14 eggs to 20 eggs during this time. Eggs hatch in four days, and are often clustered as multiple females lay their eggs in common sites. The immature stages last anywhere from 11 days to 14 days and the entire life cycle is completed in three weeks. Infestations of chorioptic scab mite tend to be higher in goats than in sheep, with up to 80 percent to 90 percent of goats in individual herds being parasitized. The mites occur most commonly on the forefeet of goats, where the largest numbers of mites and lesions are usually associated with the accessory claws. However, they also can occur higher on the foot. Lesions are generally mild and seldom draw attention.

Treatment and control of mites should focus on all animals in a herd to achieve control. Delayed egg hatch requires retreatment at 10 days to 12 days. To reduce the risk of introducing mites into herds, isolation of new animals should be practiced, with at least a week to observe the animal for signs of mange.

Fleas

Adult fleas are small (1 mm to 8 mm), wingless insects that are narrow and compressed on the sides with spines (combs) directed backwards. Most species move a great deal and remain on the host only part of the time to obtain a blood meal. The legs are well developed and are utilized to jump great distances (7 inches to 8 inches).

Fleas develop through a complete life cycle with four stages: egg, larva, pupa, and adult. Under ideal conditions, a generation can be completed in as little as two weeks. Mating takes place and eggs are laid on the host. Eggs then drop to the ground or bedding material, hatching in two days. Hatching can be delayed up to several weeks. Development of the larval and pupal stages occurs in the host’s bedding material. Larvae are very small, worm-like, legless insects with chewing mouthparts. In several weeks, they go through three larval stages, feeding on organic material. The pupal stage lasts approximately one week. The newly emerged adult flea is ready to feed on blood within 24 hrs.

There are two species that commonly infest goats: the cat flea (Ctenocephalides felis) and sticktight flea (Echidnophaga gallinacea) (Figure 7). Female cat fleas can lay up to 25 eggs per day for a month, contributing to very high densities of fleas in a relatively short time. Cases of severe anemia associated with high numbers of cat flea bites have been reported in domestic animals. The sticktight flea attaches firmly to its host usually around the face and ears. This species remains attached to its host for as long as two weeks to three weeks. Large populations of this flea may cause ulcers on the head and ears. Both of these flea species can easily spread to other animals, so special considerations of monitoring herd dogs should be implemented if fleas become a problem in a goat herd.

Ticks

Ticks harm their hosts by injuries caused by bites, resulting in blood loss and transmission of disease pathogens. Ticks can be classified in three groups: one-host, two-host and three-host ticks. Ticks that commonly parasitize goats mainly belong to the three-host group. As the name implies, three-host ticks infest three different hosts throughout their life cycle, which can make control difficult.

While ticks are not commonly found on goats, there are three species of ticks documented to parasitize goats. The three tick species are: American Dog Tick (Dermacentor variabilis), Gulf Coast Tick (Amblyomma maculatum), and Lone Star Tick (Amblyomma americanum).

The adult American Dog Tick can be identified by their reddish-brown color with silver-white markings on the back and upper body regions (Figure 8). The silver-white markings are on the scutum (u-shaped area behind the mouthparts) in females. On the male, the markings extend over the whole back. Females increase in size dramatically when fully engorged (from ¼-inch to ½-inch), resembling a gray bean.

Figure 8. Female (left) and male (right) American Dog Tick, Dermacentor variabilis. Credit: R. Grantham; Oklahoma State University.

The Gulf Coast Tick is most commonly found on goats with horns and more specifically at the base of the horns. Occasionally, some Gulf Coast Ticks are found in the ears of the animals. They are reddish brown with pale reticulations (Figure 9) and very similar to, but slightly smaller than American Dog Ticks. Gulf Coast Ticks have longer mouthparts than the American Dog Tick. The Gulf Coast tick is considered a presumed vector of Ehrlichia ruminantium, the rickettsial causative agent of heartwater, an African disease of ruminants that could enter the U.S. from the Caribbean.

Figure 9. Female (left) and male (right) Gulf Coast Tick, Amblyomma maculatum. Credit: R. Grantham; Oklahoma State University.

Lone Star Ticks are more commonly found along the withers and neck areas of goats. Occasionally, they can be found on the head and arm-pit regions. Adult females can be easily identified by the single lone spot on the back (Figure 10). Adult males have non-connecting white markings along the posterior margin. This tick has much longer mouthparts when compared to the previously mentioned ticks. Research has shown that goats can serve as reservoirs of Ehrlichia chaffeensis, which is the bacterial agent responsible for human monocytic ehrlichiosis and the primary vector is the Lone Star Tick. Care should be taken when handling goats heavily infested with Lone Star Ticks.

Figure 10. Female (left) and male (right) Lone Star Tick, Amblyomma americanum. Credit: R. Grantham; Oklahoma State University.

Xem thêm : Trabajo de parto y parto, cuidado de posparto

All of the tick species previously described can be found on goats and utilize multiple hosts, which can complicate control, since each life stage can parasitize different animals. A seasonal cycle of these ticks indicates that Gulf Coast Ticks begin to parasitize goats in early spring with the latest occurrence observed in mid-summer. The American Dog Tick and Lone Star Tick are observed on goats throughout summer months. Targeted insecticide applications should control all of these tick species, but reapplication may be warranted three weeks later. Currently, there are very few insecticides registered for goats, so extreme vigilance should be taken when selecting products to treat your goats.

Flies

Flies go through complete metamorphosis which consists of eggs, larvae, pupae and adults, with each life stage occupying different habitats (Figure 11). Flies particularly troublesome to goats include horn fly, stable fly, horse flies, house flies, blow fly, mosquitoes and black flies. These flies can be severely annoying and may affect the performance of goats. They hinder grazing and cause goats to bunch or run to get relief from the annoyance of these flies. Biting or blood-sucking flies can cause painful bites and significant irritation to goats.

Figure 11. Illustration of a fly life cycle. Credit: Langston University.

Biting Flies

Horn Flies

Horn flies (Figure 12) are primarily a pest of cattle, but occasionally seen on goats, especially when goats are co-grazing a pasture with cattle. Both male and female horn flies take blood from the host and feed from 20 times to 30 times a day. Horn flies continually stay on the animal and only leave the animal for short periods to lay eggs. Typical feeding areas on goats include the back, side, belly and legs. Horn fly populations begin building up in the spring and last until the first frost.

Figure 12. Adult horn fly, Haematobia irritans approximately 4 mm in length. Credit: Kurt Schaefer Courtesy of Bugguide.net

Stable Flies

Stable flies (Figure 13) are medium-sized flies, which resemble house flies. Stable flies feed on goats with their head up, and prefer to stay on the feet and legs of goats. Both male and female stable flies take blood from the host and have a very painful bite. Large populations of stable flies on pastured goats often cause goats to bunch and mill around. Stable fly larvae develop in moist decaying organic matter associated with spilled feed, soiled hay or straw bedding. They particularly like areas where hay bales were fed and the hay is trampled into the ground by feeding goats. Stable flies are more of a problem around barns or loafing sheds, where there is an abundant resource of decaying organic matter for them to develop in as well as vertical resting sites such as the sunny sides of barns or sheds.

Figure 13. Adult stable fly, Stomoxys calcitrans. Credit: Dan Brown Courtesy of Kansas State University.

Horse Flies and Deer Flies

There are many species of horse and deer flies (Figure 14) in U.S. Seven or eight species can be considered significant pest, depending on the location. Horse flies vary in size from ½-inch to 1.5 inches or longer. Female horse flies are vicious biters, and peak populations of one species or another occur throughout the summer months. Male horse flies do not bite. Horse and deer flies generally only complete one generation per year. Many horse flies lay their eggs around the edges of ponds and their larvae develop in the moist mud along the perimeter of the pond, making control in the larval stage impossible. Some of the most important species lay their eggs in the soil under thick layers of leaves in the heavily timbered areas. Larvae develop in the soil. Adult horse and deer flies prefer feeding on the legs and backs of animals. Heavy populations of adult horse flies can cause economic losses, but controlling them in a cost effective manner is not possible. Because the female horse fly is only on the animal for a few minutes while taking a bloodmeal, it is difficult to get enough pesticide on the animal to deter the fly from feeding. The flies may receive enough pesticide to kill them after they leave the animal, but this is difficult to determine. Because horse flies are continually emerging throughout the summer and many species have an extensive flight range, there will be flies on goats regardless of whether or not a pesticide treatment has eliminated some of the population. Horse flies are repelled by some pesticides just after spraying the animal, but this is not a practical method of protection. Recently, traps have been promoted to decrease populations of horse flies, but these traps are expensive and numerous traps are required to reduce horse flies in a relatively small area.

Figure 14. Common horse & deer flies found around livestock. Credit: R. Wright, L. Coburn & R. Grantham Courtesy of Oklahoma State University.

Mosquitoes and Black Flies

Certain species of mosquitoes and black flies species will feed on goats, but are normally not present in high enough populations for a long enough period to cause significant damage. Both of these groups of insects are most prevalent in the spring. Black fly immature stages develop only in running water in streams or rivers. Large populations sometimes occur in late spring and into early summer. Mosquito larvae develop in standing water and pest populations on goats are most often associated with water from flooding or heavy rainfall that remains for a week to ten days. Large populations sometime occur in pasture areas that hold temporary pools of water. The primary threat from mosquitoes is their ability to transmit disease.

Nuisance Flies

House Flies (Figure 15) House flies do not bite goats, as they only possess sponging mouthparts. However, they may cause extreme annoyance to animals when they are present in large numbers. House flies tend to aggregate on specific areas of the animal and can be severe nuisance pests of confined animals, especially goat kids. They often aggregate around the eyes and mouth because of the moisture secreted by the animal. House fly larvae develop in moist decaying organic matter, especially accumulated manure, rotting feed and garbage. House flies will utilize areas associated with spilled feed and hay to lay eggs similar to the life cycle of stable flies. House flies are not often pests of pastured goats unless such goats frequent loafing sheds. Good sanitation around barns is the best method of house fly control. Sprays inside buildings, referred to as premise sprays, can also be utilized to control adult house flies. Premise sprays can be used on surface areas inside of barns, where the flies will contact the insecticide residue when resting on these surfaces. Automated mist blowers can be used in barns to apply space sprays which will kill adult flies. Commercial baits can also be used to attract house flies to bait containing a pesticide. Baits typically attract only house flies and do not provide control for other fly species.

Figure 15. Adult house fly, Musca domestica. Credit: Jim Kalisch, University of Nebraska-Lincoln.

Blow Flies

Blow flies are similar to house flies and do not bite goats, but cause significant annoyance to the animals and animal operators. They tend to aggregate on animals with wounds or skin infections. Blow fly larvae develop in decaying organic matter and decomposing dead animals. The primary source of blow fly attraction to animals is bacterial activity on the animal. Sanitation around barns is the best method of preventing a blow fly population from becoming significant. Special care should be taken during kidding season to clean up afterbirth, since this is highly attractive to blow fly populations.

Control of Flies

A significant portion of fly problems around livestock buildings can be alleviated through sanitation and proper manure management. This will be unsuitable for fly production. Regular removal of bedding material and spilled feed is a good way to prevent fly populations from becoming significant.

The utilization of fly parasitoids sometimes known as ‘fly predators’ works well in combination with a good sanitaion program. Several companies produce and market these parasitoids to livestock operators and can be cost effective when used properly. These parasitoids are small wasps that target lay their eggs inside the fly pupae. Proper dissemination is critical to preventing a fly outbreak, and the best practice for these ‘fly predators’ to be successful is the practice of releasing these before fly populations become noteworthy. If fly parasitoids are utilized, insecticide use should be limied. Insecticides kill parasitoids just like it does flies.

Insecticide-based control may be necessary when flies become extensive around goat operations. The only products approved for on-animal application to goats are permethrin or pyrethroid-based products, with best results from synergized pyrethroid products containing piperonyl butoxide (PBO). Goat operators have more options when just treating the barns and these are sometimes referred to premise sprays. The best option for a premise spray is to use a residual spray that remains effective for some length of time, compared to a non-residual product such as pyrethrum. When applying residual sprays, be sure to treat vertical fly resting sites such as barn walls. Make sure the surface is not wet or greasy when applying the product. Recently, more livestock operators who house animals in barns for the majority of the time are utilizing automated mist systems. These can be effective, but care should be taken not to overapply products, especially when animal feed or hay is present. The overuse of these systems also can lead to insecticide resistance. Goat operators with these systems should set these to be active when the flies are active.

Summary

A comprehensive management plan for external parasites on goats will be variable and unique to individual goat operations. The key to a successful parasite management program is continual monitoring of the herd. A summary (Table 1) of recommended practices for each pest complex is given with peak seasonality for each goat pest. The combined approach of an integrated pest management program is the most economical and environmentally sound tactic. The overall goal of a sound external parasite program is to manage the pests in a manner that reduces stress to the animals, as well as reduce the risk of pathogen transmission from the parasites.

Table 1. Summary of control recommendations for certain external parasites found of goats.

Justin TalleyDepartment of Entomology and Plant Pathology

Nguồn: https://buycookiesonline.eu

Danh mục: Info

This post was last modified on December 13, 2024 11:59 am